The Original Tree Huggers: Let Us Not Forget Their Sacrifice

Blog by: Rucha Chitnis, Former WEA South Asia Program Director.

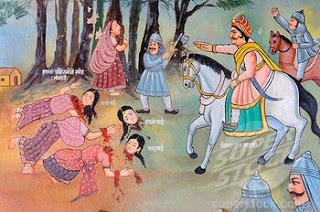

Nearly 280 years ago, the sacrifice of a brave woman, Amrita Devi, would have ripple effects in one of India’s most vibrant environmental movements called the Chipko Andolan in the 1970s. Amrita Devi belonged to the Bishnoi community that is known for its great love for conservation. The Bishnoi faith respects the sanctity and sacredness of all forms of life and their tenets include prohibition on killing animals and felling of green trees. Bishnois also worship the Khejri tree, Prosopis cineraria, considered a critical life force in these desert communities.

Nearly 280 years ago, the sacrifice of a brave woman, Amrita Devi, would have ripple effects in one of India’s most vibrant environmental movements called the Chipko Andolan in the 1970s. Amrita Devi belonged to the Bishnoi community that is known for its great love for conservation. The Bishnoi faith respects the sanctity and sacredness of all forms of life and their tenets include prohibition on killing animals and felling of green trees. Bishnois also worship the Khejri tree, Prosopis cineraria, considered a critical life force in these desert communities.

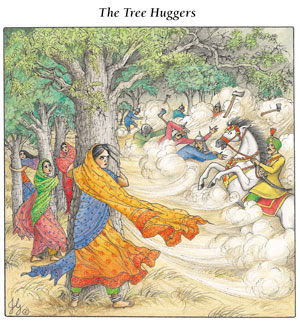

Illustration by Jillian Gilliland

When the king learned about the carnage, he was repentant and forbade any killing of animals and cutting of trees in the Bishnois territories. Even to this day, one can spot the endangered Black Buck, peacocks and other wild life and tree cover where the Bishnois communities live in Rajasthan. It is no wonder that the Bishnois are considered as among the earliest conservationists in the world.

“Soil is ours. Water is ours. Ours are these forests. Our forefathers raised them. It’s we who must protect them.” A song from the Chipko Movement in India

The Chipko Movement is a great example of a Gandhian movement that was based on nonviolent principles of satyagraha. Chipko means to hug, and this movement is synonymous with the enduring images of rural women hugging their community trees to stop rampant deforestation.In the Garhwal Himalayan region of Uttarakhand in the 70s, there was rapid environmental degradation due to commercial logging. It became clear, especially to women, that logging was destroying their forests and threatening their access to key forest resources needed for their daily sustenance.

Archival photo of the Chipko Movement, where women battled guns and threats to protect their forests.

Soon villagers began organizing themselves in small groups to organize against logging.A pioneering Gandhian grassroots activist, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, mobilized communities to stop the destruction of the forests. He was joined by hundreds of women, who were on the front lines of the resistance—marching and rallying to protect their community forests and formed human chains to hug towering old growth trees. This kind of environmentalism was inherently linked to their survival; the women recognized that their livelihoods and wellbeing were intertwined with ecological protection

“This movement of the poor women was not a conservation movement per se, but a movement to demand the rights of local communities over their local resources. The women wanted the first right over the trees, which they said were the basis for their daily survival. Their movement explained to the people of India, that not poverty, but extractive and exploitative economies were the biggest polluter,” writes Sunita Narain, director of Center for Science and Environmental in New Delhi. The impact of the Chipko movement had spread far and wide beyond the state of Uttarakhand and led to the government issuing a ban on felling of trees for 15 years until the green cover depleted by deforestation was restored. And the legacy of tree hugging continues to this day, as do the challenges for people’s access to community forests and threats from ongoing forest degradation.

“Forest is Our Mother. Our life sustains on her.

Adivasi women play a crucial role in Jharkhand’s Save the Forest Movement

Suryamani, second from left, is one of the eloquent and passionate leaders of Save the Forest Movement

In India, mining, hydroelectric and nuclear power projects, industries, among others, are displacing thousands of farmers, fisher folks, pastoralists, artisans and indigenous people from their homelands.Historian, Ramachandra Guha notes how the environmental movement in India arose out of the imperative of human survival. “This was environmentalism of the poor,” he wrote. This“empty-belly environmentalism,” where women and girls in India, undoubtedly the poorest, who are most acutely affected by hunger because of the multi-faceted discrimination they face, find themselves on the frontlines of many people’s movements against land and other resource grabs, not out of choice but from the sheer will to protect their livelihoods and dignity, their identity and culture.

From the brave sacrifice of one Bishnoi woman to the long movement building of women of the Chipko Movement to the ongoing struggles of adivasi women in the Save the Forest Movement in Jharkhand—they all exemplify why it is crucial for women to have equal access and control over natural resources. Environmental movements globally can learn from these bold uprisings of women and make greater commitments to build more diverse and inclusive movements to ensure that indigenous women and women of color are active participants in these struggles and are able to share their vital experiences and perspectives on environmental protection.

As I was said goodbye to Suryamani in her village in Jharkhand, I asked her what changes she had noticed in the forests since the Save the Jungle Movement began. “Our forests are regenerating, she said. “The birds and animals are returning, and we also spotted a leopard.” I also wondered what the mainstream urban community could learn from the mobilizations of adivasi communities in Jharkhand. “Our life is bound with Nature. You can learn from that,” she said.

The Indigenous Mahua tree is considered as a boon to adivasi communities

Wow ..Such Motivating stories gives a hope for our better future. I have seen videos/pictures where Bishnoi mothers along with their child breast feed animals ..I salute to such wonderful people. In Hinduism its said “You are what you desire..as is your desire so is ur itention, as is ur intention so is your will, as is ur will, so is ur deed, as is ur deed so is ur destiny” Upanishads

[…] perkembangannya, Raja Jodhpur, sebagaimana dikutip dari Women’s Earth Alliance, mengirimkan tentara ke Desa Bishnois untuk menebang pohon hijau guna membangun istana barunya. […]