Running the Salmon Home: The Winter-Run Chinook Salmon

This blog is part of a series on the Winnemem Wintu’s Run4Salmon, a two-week long prayerful event and call to action for public awareness about the need to restore the endangered winter-run Chinook salmon to the McCloud River in Northern California. To learn more about the Winnemem Wintu and this sacred relationship with Salmon, read our first post in this series here.

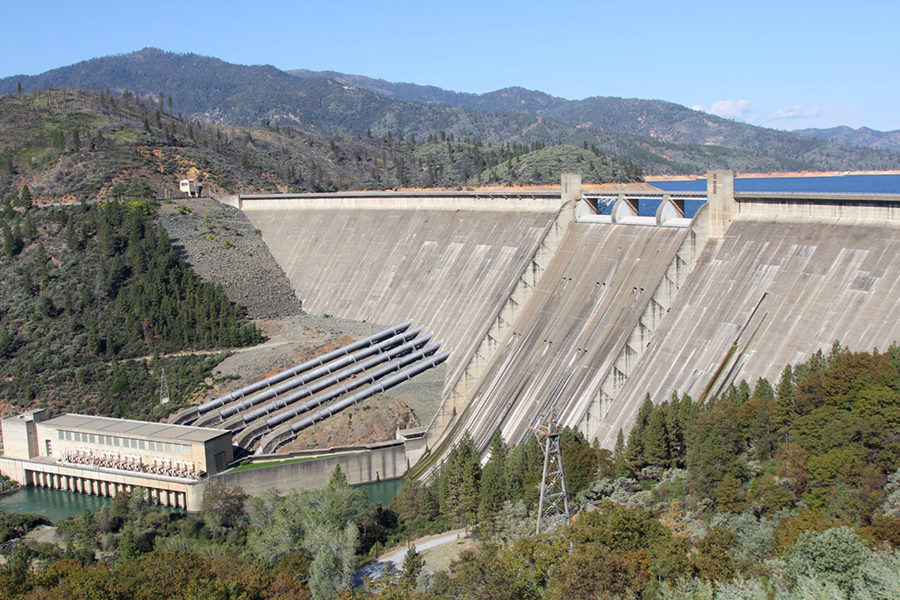

With a capacity of 4.5 million acre-feet, Shasta Lake is California’s largest reservoir, and provides about 17% of the state’s overall capacity for water storage. In the wake of the recent and worst drought in California history –– which lasted for five years, affected 90% of the state, and prompted Governor Jerry Brown to declare a three-year-long drought state of emergency –– large-scale infrastructure projects like the Shasta Dam are often applauded as remedial efforts to respond to water shortages, while the environmental, ecological, and cultural consequences of these projects go underrepresented or unaddressed. In Northern California, this indifference is evidenced by the lack of urgency expressed by both the government and the general public in responding to the threats that the proposed raising of the Shasta Dam poses towards human and non-human life in the area.

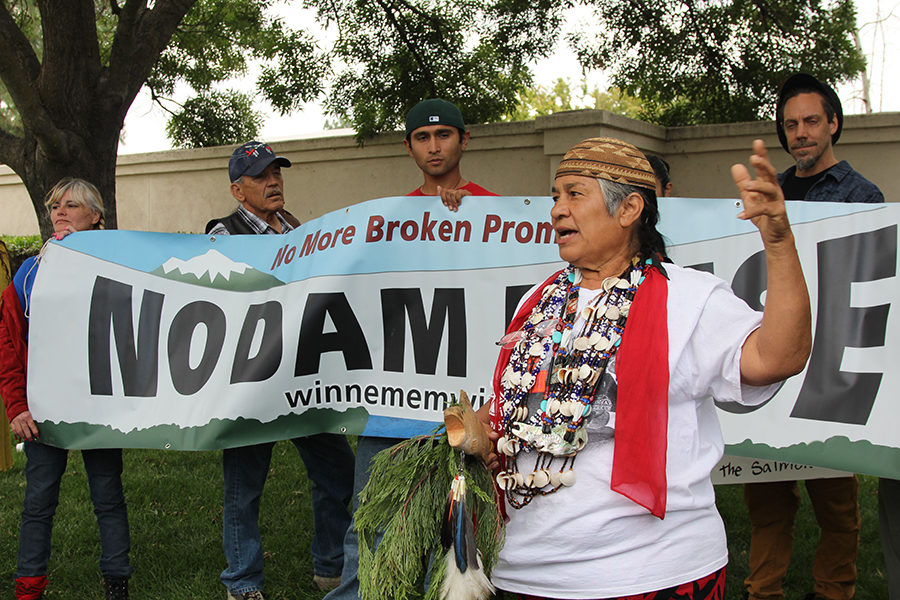

Chief Caleen Sisk at the 2016 Run4Salmon. Photo: Toby McLeod

Where have the Salmon gone?

Chinook salmon are anadromous fish, meaning they migrate upstream as adults to lay and fertilize their eggs in cold water and return downstream as juveniles to mature in the ocean. In the early nineteenth century, four distinct populations of Winter-Run Chinook Salmon flourished in the Sacramento River system. The fish spawned in upper tributaries for thousands of years –– in the McCloud, Pit, and Little Sacramento Rivers –– but California’s waterways and wetlands were drastically altered with the influx of Gold Rush settlers and the westward expansion of the American colonial project. In the mid-twentieth century, construction of the Shasta Dam blocked the salmon’s traditional spawning path along the river system and permanently altered the geological and ecological makeup of the region. Furthermore, above the dam, the rapid flood of water into the Shasta reservoir inundated homelands, burial grounds, and sacred sites of the land’s Native peoples –– including the Winnemem Wintu –– while water levels below the dam decreased, substantially reducing the river system’s ability to support the wildlife that depended on it.

In 1871, the Federal Government created the National Fish Hatchery System to manage the rapid population decrease of once-abundant fish populations nationwide. The first national fish hatchery, the Baird Hatchery, was built on the McCloud River. While these hatcheries have certainly been instrumental in preventing the extinction of countless species –– including the Winter-run Chinook –– they also contribute to decreased levels of genetic diversity and prevent the fish from fully developing their natural survival instincts.

Despite these early conservation efforts, Winter-run Chinook Salmon were listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act in 1994. Today, only one of the original four populations that once flourished in the Sacramento River system remains, and as their access to cold-water tributaries like the McCloud River is still obstructed by the Shasta Dam, Winter-Run Chinook are left with one short stretch of the Sacramento River as their only available natural breeding waters. As a result, only 5% returned to the rivers to spawn in 2014, and only 1% returned to spawn in 2015.

Shasta Dam. Photo: Toby McLeod.

The Winnemem’s fight to restore this sacred relationship

In 2005 the Winnemem Wintu tribe, to whom salmon are considered sacred, discovered that Winter-run Chinook eggs that had been sent to New Zealand’s South Island from the Baird Hatchery decades ago have spawned and flourished in the Rakaia River –– the only other place in the world where this has happened. According to the Winnemem’s proposed plan for salmon restoration, genetic diversity and necessary adaptive traits have been preserved in the Rakaia River salmon in ways that were impossible in the McCloud River following construction of the Shasta Dam and alteration of the surrounding waterways. After visiting the local Maori tribe and the salmon in New Zealand, the Winnemem have proposed that salmon from the Rakaia River be used to reintroduce Winter-run Chinook back into the Sacramento River system.

The Winnemem Wintu are advocating for spiritual and cultural awareness to be practiced in the development of this restoration plan. The tribe hopes that repatriation of their sacred salmon back to the McCloud River waters will be recognized as an act of restoring ecological health and spiritual balance to the homelands they have shared with the Winter-run Chinook for thousands of years.

The McCloud River in historical Winnemem homelands, which would be further affected by the proposed raising of Shasta Dam. Photo: Jessica Abbe.

The Run4Salmon

Restoring wild salmon to our waters is crucial to protecting the biological health of river ecosystems, as well as supporting the traditional and spiritual ways of life of the Indigenous peoples who lived on this land, with these same fish, long before western invasion and settlement intruded and put these relationships in jeopardy. The 2017 Run4Salmon, which will begin in Ohlone territory here in the Bay Area on September 8th, is part of the Winnemem Wintu tribe’s ongoing effort to bring the sacred salmon back home.

A traditional Winnemem dugout canoe on the McCloud River during the 2016 Run4Salmon. Photo: Jessica Abbe.

For more information on the Run4Salmon and ways to get involved, stay tuned for the next post in our Running the Salmon Home series. You can also follow the Run4Salmon journey on Instagram.

And to learn how you can stand alongside the Winnemem Wintu in their immediate efforts to bring the salmon home, visit here.

Blog post by Fiona McLeod, WEA Program + Operations Intern