These Indigenous women are organizing a movement to stop a deadly pipeline

Water Walk in opposition to the Mountain Valley Pipeline, May 2021. Video: Mothers Out Front.

When Desirée Shelley moved from Maryland to a rural valley near Roanoke, Virginia in 2017, she knew plans were underway to build a methane pipeline that would pass just eight miles from her house. But Desirée thought she and her family would be safe anyway. The project ― called the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) ― was in a different watershed, and so would not contaminate the well that supplies drinking water for her, her husband and their two daughters, now ages three and five.

But the more Desirée learned about the project, the more deeply it concerned her. Development of the Mountain Valley Pipeline entails laying pipe underground for 303 miles from northwestern West Virginia to southwestern Virginia, where Desirée and her family live. Along the way, the pipeline crosses the Blue Ridge Mountains, including Catawba Mountain, which Desirée sees from the front of her house.

Catawba Mountain, VA

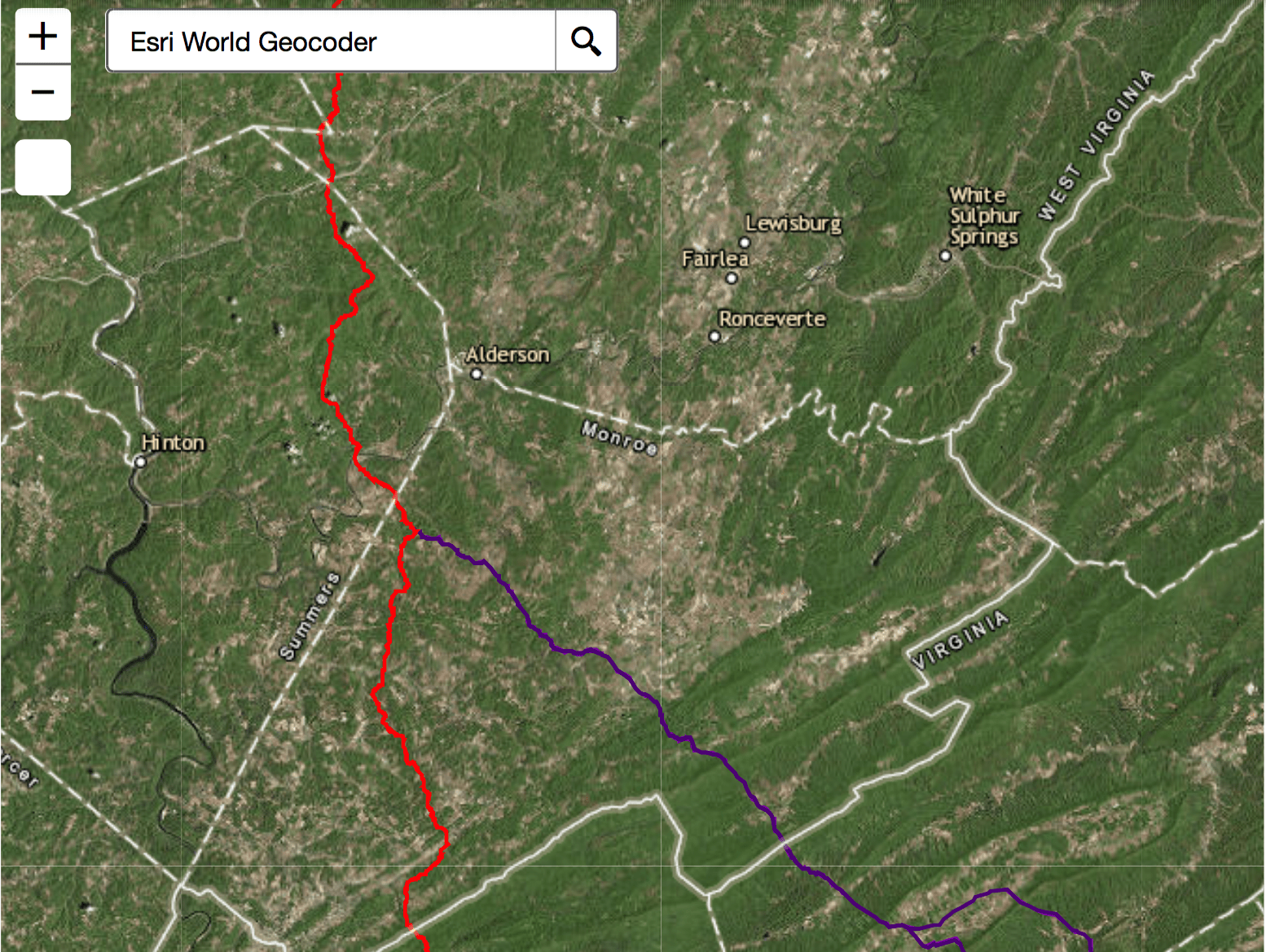

Click here to view an interactive map of the Mountain Valley Pipeline route and its potential environmental impacts. Photo: Indian Creek Watershed Association

Catawba Mountain is covered by dense forests, traversed by meandering streams, and full of karst caves and sinkholes. The mountain is also very steep. "They were going to bury 42-inch pipe and send high-pressure gas through it," says Desirée, who has a background in natural resources management. "That's one of the largest diameter gas pipes ever built, and it's never been tested on steep terrain." She had visions of gas leaks and explosions as well as landslides as heavy rains washed soil from the destabilized slopes.

As a mother with young children, though, Desirée's capacity to take action on the MVP was limited. In 2018, the year after her family moved to Virginia, crews began laying pipe up Catawba Mountain. "It was kind of traumatizing and very, very frustrating," says Desirée, who drove past the work site regularly while taking her oldest daughter to story time at the library. "They were slashing down trees and clearing land." And sediment from the aftermath of that destruction is already a problem.

During severe rainstorms, sediment overwhelms the measures intended to safeguard waterways. "It's a huge, steep incline with sediment pouring down into streams ― if you live here you see all that," Desirée says. All that sediment threatens aquatic life, including the endangered Roanoke logperch, and water quality.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline also raises deep-seated environmental justice issues. "The rural parts of Virginia get much less attention politically than other areas of the state," Desirée says. , adding that the populous areas in the north near Washington DC dominate state politics. "It was easy to push the pipeline through ― living here feels very much like you're in a Sacrifice Zone."

Desirée, who is Monacan, was even more distressed when she learned that the Mountain Valley Pipeline's route encroached on sacred Indigenous sites. "Part of the reason we moved here was that we wanted our kids to have a connection to ancestral homelands," says Desirée, whose third baby was born this summer.

Landowners on Bent Mountain, which is about half an hour from Desirée's house, told her of multiple Monacan burial mounds as well as pottery and other artifacts on their properties, and she went to see for herself. "It's important for us to go there and pray, and to honor, respect and protect our ancestors," Desirée says.

These sacred sites are not officially recognized, rather knowledge of them has been passed down through generations locally. "There's been erasure of a lot of East Coast tribes," Desirée says, adding that British colonialists displaced, fragmented, and re-wrote the narratives of Indigenous peoples. "Documentation of our history has been a challenge."

A turning point in Desirée's work to protect rural communities, land and water as well as sacred Indigenous sites from the Mountain Valley Pipeline came in 2019, when she got a job as a climate justice organizer with Mothers Out Front, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting children from climate change. In addition to the MVP’s other devastating environmental impacts, the project will also enlarge Virginia's carbon footprint. "Mountain Valley Pipeline will double emissions for the state," Desirée says, explaining that methane is a greenhouse gas with 25 times the potency of carbon dioxide for trapping heat in the atmosphere. Now, giving voice to other mothers' concerns about ― and raising awareness of ― the pipeline's environmental impacts is part of her job.

Desirée Shelley, WEA Leader (U.S. Grassroots Accelerator), Mothers Out Front. Photo: Desirée Shelley

Another turning point came last year, when Desirée joined forces with Crystal Cavalier, a citizen of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation who lives in Mebane, North Carolina. The two women connected via the Alliance of Native Seed Keepers, which preserves and propagates food plants grown by Indigenous peoples. "We care for our seeds like they were our children," says Crystal, whose blended family with her husband includes five children ages 14 to 22. "They tie us to the land and to our ancestors ― these cultures were taken from us and this is a way to heal."

In 2018, Crystal was alarmed when she learned that the Mountain Valley Pipeline planned to add an extension from southwest Virginia into North Carolina. Called MVP Southgate, this 70-mile pipeline extension would be the first step in linking the project to the coast for exporting methane overseas. "I started fighting it three years ago," Crystal says. "It's going in five miles from where I live."

Crystal Cavalier, WEA Leader (U.S. Grassroots Accelerator), 7 Directions of Service. Photo: Crystal Cavalier.

The seeds Crystal keeps include many varieties of beans and corn, and she grows them the way her ancestors did, planted in mounds and free of pesticides. She worries that methane leaks from the Southgate extension will taint the crops that help keep her culture alive. "What goes into the air gets into the waterways and soil, and you can't plant Indigenous food if the pipeline poisons the ground and water." she says.

Much of the Mountain Valley Pipeline has already been laid in Virginia. But there’s still time to stop the Southgate extension from even beginning. "It's another environmental justice issue ― Southgate goes through a lot of Black and Indigenous communities, and most people don't know it's coming," Desirée says. "I want to keep what happened in Virginia from happening there."

The Mountain Valley Pipeline took property by eminent domain, Desirée explains, adding that most of the people in its way just settled because they couldn't afford attorneys to fight the project. "It's not really about race, it's about class," adds Crystal, who co-founded 7 Directions of Service, an Indigenous-led, multi-racial organization advocating for low-income, working-class and BIPOC communities in North Carolina. "It affects Black, white and Indigenous alike who are economically challenged."

As in Virginia, the pipeline's proposed route through North Carolina includes sacred places. "It goes through a lot of Indigenous burial mounds on private property and an African American slave cemetery," says Crystal, who recently began a job as an organizer with the Native Organizers Alliance. "What to them is a pile of rocks, to us is a sacred site that is part of our ancestors."

Crystal and Desirée's first collaboration was a virtual rally, held in the summer of 2020 to protest the Southgate extension. Many other community activists and coalitions joined them, including 7 Directions of Service, Mothers Out Front, the Virginia environmental organization Water is Life, Protect It, and the Southwest Virginia Poor People's Campaign.

Then, in the fall of 2020, a mutual friend recruited Crystal and Desirée to participate in the Women's Earth Alliance (WEA)U.S. Grassroots Accelerator ― a partnership with Sierra Club ― which trains women leaders to scale up their climate and environmental initiatives. "It opened up a new view of how to be a leader ― it's a holistic approach to organizing," Desirée says.

She was rejuvenated by WEA's emphasis on the need for self-care. "It wasn't the typical 'you have to kill yourself to succeed,'" she continues. "I can't be a successful leader if I can't show women how to take care of themselves." And the power of women coming together to protect the environment resonated with both Crystal and Desirée. "Women have traditional wisdom and an innate connection with the Earth," Desirée says. "I really like WEA," Crystal adds. "The women there have good spirits and souls."

Crystal and Desirée are now putting the lessons learned at WEA – from campaign strategy to fundraising to long-term goal setting ― into practice. "WEA really puts you on track: what is my end goal and how can I get there?" Desirée says. Crystal puts it this way: "We're able to amplify our work ― WEA helps you look more at the horizon."

Water Walk in opposition to the Mountain Valley Pipeline, May 2021. Photo: Crystal Cavalier.

In May 2021, Crystal and Desirée led an in-person Water Walk along the proposed route of the Southgate extension to raise awareness of the need to protect the land, water, sacred sites and people there. More than 90 teams of walkers, runners, cyclists, and paddlers participated. "It was really beautiful," Crystal says. "We walked along the three main rivers that the pipeline will cross." The activists also knocked on doors along the Southgate’s route to alert people that it was coming through. Crystal and Desirée are planning a second Water Walk this summer.

They also have even bigger plans. "In fighting the pipeline and revitalizing cultural lifeways like agriculture, we want to connect our past ― our ancestors and their teachings ― to our present and future. Protecting sacred places from forests and waters to the sites where our ancestors are buried is essential to preserving and revitalizing our culture and history," Desirée says. "We want to make these connections and put it all together to create a larger movement." They also want to make their voices heard more widely. Says Crystal, "Our goal is national awareness."

Written by: Robin Meadows

Filmmakers Making A Social Impact: Why & How Filmmaker Chevaun Toulouse Is Helping To Change Our World

https://medium.com/authority-magazine/filmmakers-making-a-social-impact-why-how-filmmaker-chevaun-toulouse-is-helping-to-change-our-8149384ccdbe

Documentary Series ‘Great Lakes Untamed’ is a Stunning Look at the Fragility of Nature

https://www.seechangemagazine.com/documentary-series-great-lakes-untamed-is-a-stunning-look-at-the-fragility-of-nature/

Native biologists speak out

https://indiancountrytoday.com/newscasts/10-20-2022

An Indigenous Perspective on Reconnecting With the Land

https://www.yesmagazine.org/opinion/2022/10/14/land-conservation-indigenous-biodiversity

TVO launches ‘Great Lakes Untamed’ series Sept. 26

https://www.manitoulin.com/tvo-launches-great-lakes-untamed-series-sept-26/

BBC to TVO: Canadian director comes home with Great Lakes doc series

https://www.elliotlakestandard.ca/entertainment/bbc-to-tvo-ottawa-director-comes-home-with-great-lakes-doc-series/wcm/93f04ded-75ee-484f-884b-b1114c7fe3bf

Direct Action Blog: Swamp Adventures Coming Full Circle

https://ocean.org/blog/direct-action-blog-swamp-adventures-coming-full-circle/